Calculus I

Derivatives of Certain Functions

Let’s now go over the derivatives of some common functions that you’ll see often.

First, let’s go over the derivatives of trigonometric functions. The basis of all of these derivatives will be the derivative of \(\sin(x)\), so we will cover that one first. Because \(\sin(x)\) is its own function that isn’t based on any other, there’s no rule that we can use. Let’s use the definition of the derivative instead.

\[\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h} \\\]We can use the addition formula for sine to expand the \(\sin(x+h)\).

\[\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x)\cos(h)+\cos(x)\sin(h)-\sin(x)}{h} \\ \lim_{h \to 0} \bigg[\frac{\sin(x)\cos(h) -\sin(x)}{h}+\frac{\cos(x)\sin(h)}{h}\bigg] \\ \lim_{h \to 0} \bigg[\frac{\sin(x)\cos(h) -\sin(x)}{h}\bigg]+\lim_{x \to 0}\bigg[\frac{\cos(x)\sin(h)}{h}\bigg] \\ \lim_{h \to 0} \bigg[\frac{\sin(x)(\cos(h) -1)}{h}\bigg]+\lim_{x \to 0}\bigg[\frac{\cos(x)\sin(h)}{h}\bigg]\]Because \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) are not dependent on the first and second limit, we can pull them outside.

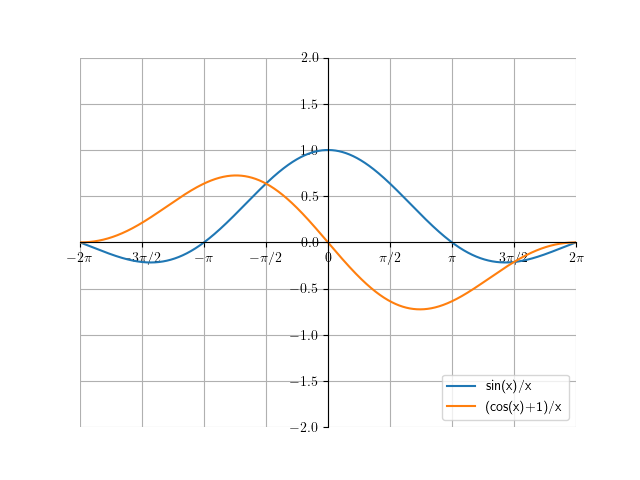

\[\sin(x) \lim_{h \to 0} \bigg[\frac{\cos(h) -1}{h}\bigg]+ \cos(x) \lim_{x \to 0}\bigg[\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\bigg]\]Now, we just have to figure out the first and second limit. Unfortunately, plugging \(h=0\) into both of the limits gets us \(\frac{0}{0}\). Let’s graph \(y=\frac{cos(x)-1}{x}\) and \(y=\frac{sin(x)}{x}\):

We can see that as \(x\) approaches 0, \(\frac{\cos(x)-1}{x}\) approaches 0 and \(\frac{\sin(x)}{x}\) approaches 1.

\[\sin(x) \lim_{h \to 0} \underbrace{\bigg[\frac{\cos(h) -1}{h}\bigg]}_ {=0}+ \cos(x) \underbrace{\lim_{x \to 0}\bigg[\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\bigg]}_ {=1} = \cos (x)\]We have shown that the derivative of \(\sin(x)\) is \(\cos(x)\). From that, we can also prove the derivative of cosine. We only need to know the following identities that relate sine to cosine:

\[\sin(x+\frac{\pi}{2}) = \cos(x) \\[0.5em] \cos(x+\frac{\pi}{2}) = -\sin(x)\]These can be proved using the sine and cosine addition formulas. To find \(\frac{d}{dx} \cos(x)\), let’s rewrite \(\cos(x)\) as \(\sin(x+\frac{\pi}{2})\) and use chain rule. Keep in mind that we know the derivative of \(\sin(x)\) is \(\cos(x)\).

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} \cos(x) &= \frac{d}{dx} \sin(x+\frac{\pi}{2}) \\ &= \cos(x+\frac{\pi}{2}) \cdot \frac{d}{dx} \bigg[x+\frac{\pi}{2} \bigg] &= \cos(x+\frac{\pi}{2}) \end{align*}\]Which, we know from the identity above, is equal to \(-\sin(x)\). Thus,

\(\frac{d}{dx} \cos(x) = -\sin(x)\)

Now that we know the derivatives of sine and cosine, we can find the derivative of tangent:

\[\frac{d}{dx} \tan(x) = \frac{d}{dx}\frac{\sin(x)}{\cos(x)} \\\]because \(\tan(x) = \left(\frac{\sin(x)}{\cos(x)}\right)\). From the quotient rule:

\[= \frac{\cos(x)\cos(x)+\sin(x)\sin(x)}{\cos^2(x)} \\ = \frac{\cos^2(x)+\sin^2(x)}{\cos^2(x)} \\\]Using the pythagorean identity, we can simplify the numerator, and find our final answer:

\[= \frac{1}{\cos^2(x)} \\ = \sec^2(x)\]Because \(\csc(x)\), \(\sec(x)\), and \(\cot(x)\) are all equal to reciprocals of other trigonometric functions, we can just use quotient rule for all of them.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} \csc(x) &= \frac{d}{dx} \frac{1}{\sin(x)}\\ &=\frac{\sin(x)(0)-(1)\cos(x)}{\sin^2(x)} \\ &=-\cot(x)\csc(x) \end{align*}\] \[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} \sec(x) &= \frac{d}{dx} \frac{1}{\cos(x)}\\ &=\frac{\cos(x)(0)-1(-\sin(x))}{\cos^2(x)} \\ &=\sec(x)\tan(x) \end{align*}\] \[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} \cot(x) &= \frac{d}{dx} \frac{\cos(x)}{\sin(x)}\\ &=\frac{\sin(x)\cdot-\sin(x)-\cos(x)\cdot\cos(x)}{\sin^2(x)} \\ &=\frac{-\sin^2(x)-\cos^2(x)}{\sin^2(x)}\\ &=\frac{-1(\sin^2(x)+\cos^2(x))}{\sin^2(x)}\\ &=\frac{-1(\sin^2(x)+\cos^2(x))}{\sin^2(x)}\\ &=-\csc^2(x) \end{align*}\]Now, let’s go over the derivative of \(\ln(x)\). Remember that \(\ln(x)\) is the logarithm with base \(e\). Because we don’t have an easy formula or rule for this, let’s use the definition of the derivative:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} \ln(x) &= \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\ln(x+h)-\ln(x)}{h} \\ \end{align*}\]Using logarithm properties, we can combine the \(\ln\)s in the numerator:

\[\begin{align*} &=\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{\ln(\frac{x+h}{x})}{h} \\ &=\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{1}{h}\ln(1+\frac{h}{x})\\ \end{align*}\]Using another logarithm property:

\[=\lim_{h \to 0} \ln\Bigg(\bigg(1+\frac{h}{x}\bigg)^{\frac{1}{h}}\Bigg)\\\]Now, we can see that this is fairly close to the definition of \(e\), which says that \(e^x = \lim_{n \to \infty} \bigg(1+\frac{x}{n}\bigg)^n\). However, one key difference is that in the definition of \(e\), the limit goes to \(\infty\). To make this more similar, let’s make a substitution where \(u = \frac{1}{h}\):

\[\begin{align*} &=\lim_{u \to \infty} \ln\Bigg(\bigg(1+\frac{1}{xu}\bigg)^{u}\Bigg)\\ &=\lim_{u \to \infty} \ln\Bigg(\bigg(1+\frac{\frac{1}{x}}{u}\bigg)^{u}\Bigg)\\ \end{align*}\]Now, we can use the definition of \(e\).

\[\begin{align*} &=\ln(e^\frac{1}{x})\\ &=\frac{1}{x} \end{align*}\]The derivative of \(\ln(x)\) is\(\frac{1}{x}\).

The final fact to know is an important one: \(\frac{d}{dx} e^x = e^x\). In other words, the derivative of \(e^x\) is itself. This is incredibly rare - in fact, \(ce^x\) (where \(c\) is a constant) are the only functions whose derivative is itself. This is why \(e^x\) is so incredibly important to calculus.