Precalculus

Trigonometry

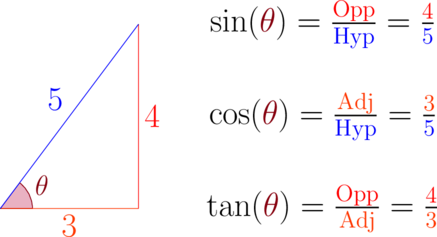

In geometry, you learned about the three common trigonometric functions: sine, cosine, and tangent. Let’s do a little bit of review:

To get the sine, cosine, or tangent of any angle, first create a right angle. One of the angles will be 90°, and one of the other angles should be the angle whose trigonometric function output we want to find. For sine, take the length of the side opposite the angle and divide that by the length of the hypotenuse. Cosine and tangent work the same, except cosine is adjacent divided by hypotenuse and tangent is opposite divided by adjacent.

Before moving forward, it’s important to have a firm understanding of radians. A degree is a unit measurement for an angle, with 360° being a full circle and 180° being a straight line. A radian is a similar measurement for a degree, except it is in terms of \(\pi\).

0 degrees corresponds to 0 radians. While 360 degrees is a full circle, 2pi radians is also a full circle. From those two facts, we can fill in the blanks. A right angle in degrees is \(\frac{360}{4}\), and a right angle in radians is \(\frac{2\pi}{4} = \frac{\pi}{2}\). The formula for converting degrees to radians is

\[\text{radians} = \text{degrees} \cdot \frac{\pi}{180}\]The formula for converting radians to degrees is

\[\text{degrees} = \text{radians} \cdot \frac{180}{\pi}\](table for degrees and radians)

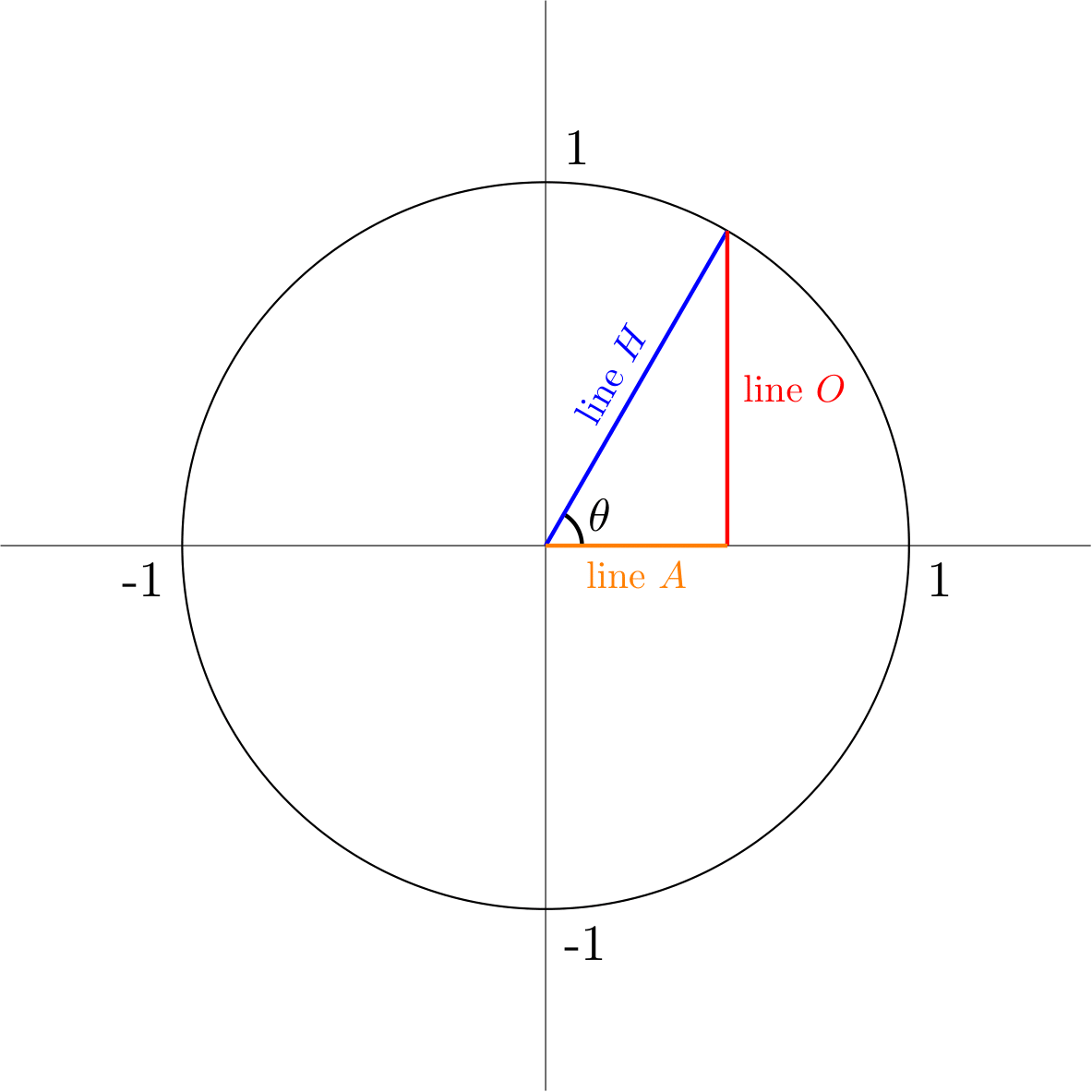

Now, let’s look at sine, cosine, and tangent as functions instead of geometrically. Let’s look at the sine function. The sine function takes in an angle measurement (usually in radians) and will output a number between \(-1\) and \(1\). That number is the ratio of the opposite side to the hypotenuse. To find out the shape of this graph, it is helpful to look at a circle. Take a look at the following circle with radius 1 (known as a unit circle, with triangles within it:

No matter the angle \(\theta\), line \(H\) stays at a length of 1. This is because of the nature of equidistance in circles. However, lines \(O\) and \(A\) varies in length. Let’s zoom into one instance of this circle:

It seems like a right triangle pops out of nowhere.

Now, using our definition from earlier, we can clearly see that \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{\text{length of line }O}{\text{length of line }H}\). Because the length of line \(H\) is always 1, we can say that \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{\text{length of line }O}{1}\). This is an important discovery - it shows us that \(\sin(\theta)\) is directly equal to the height of line \(O\).

Using this information, we can follow \(\theta\) around the full \(2\pi\) radians to see the following:

This gives us the shape of \(\sin(\theta)\).

Now, let’s do a similar process for cosine.

Here, we can see that \(\cos(\theta)\) is equal to the length of line \(A\) divided by the length of the hypotenuse. Again, because the length of the hypotenuse is always \(1\) no matter the value of \(\theta\), \(\cos(\theta)\) is equal to the length of line \(A\)

Here’s the shape of the sine and cosine curve:

Something to notice is how the graphs of sine and cosine will repeat. Because the unit circle has a circumference of \(2\pi\), it means that the values for sine and cosine will repeat every \(2\pi\) units. This is known as the period of the curve. The period is how long it takes for the curve to repeat its pattern.

Now, let’s talk about tangent. \(\tan(x)\) is defined to be \(\sin(x)\) divided by \(\cos(x)\). This is why the tangent of an angle is equal to opposite over adjacent.

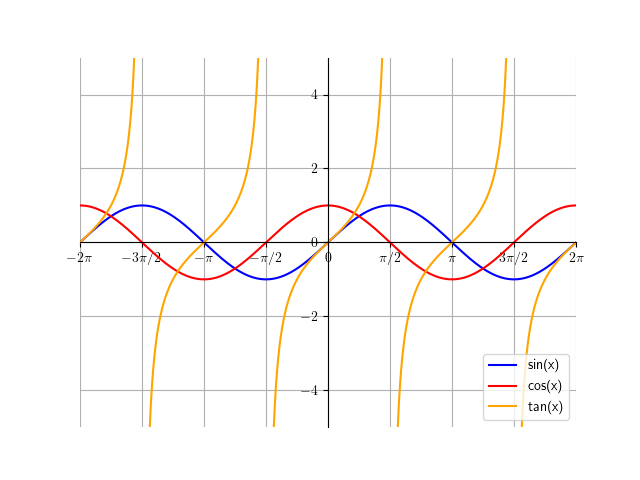

\[\begin{align*} \sin(x) &= \frac{\text{Opp}}{\text{Hyp}}\\ \cos(x) &= \frac{\text{Adj}}{\text{Hyp}}\\ \tan(x) &= \frac{\sin(x)}{\cos(x)}\\ \tan(x) &= \frac{\frac{\text{Opp}}{\text{Hyp}}}{\frac{\text{Adj}}{\text{Hyp}}}\\ \tan(x) &= \frac{\text{Opp}}{\cancel{\text{Hyp}}}\cdot\frac{\cancel{\text{Hyp}}}{\text{Adj}}\\ \tan(x) &= \frac{\text{Opp}}{\text{Adj}} \end{align*}\]This is the graph of \(\tan(x)\) overlaid over the graphs of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\). You can see how when \(\sin(x)\) is 0, \(\tan(x)\) is 0 (because 0 divided by anything is 0), and when \(\cos(x)\) is 0, \(\tan(x)\) has no value (because anything divided by 0 is undefined).

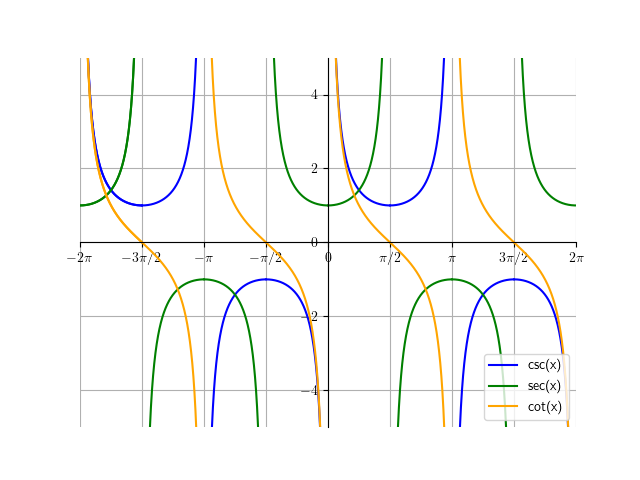

There are three other functions to know: \(\csc(x)\), \(\sec(x)\), and \(\cot(x)\). They are fairly simple:

\[\csc(x) = \frac{1}{\sin(x)}\] \[\sec(x) = \frac{1}{\cos(x)}\] \[\cot(x) = \frac{1}{\tan(x)}\]Here are their graphs:

And here are the graphs of all 6 functions overlaid: