Calculus I

Integration

Now that we have an understanding of both antiderivatives and integrals, we can explore the connection between them. By the end of this chapter, we’ll see see how the area under a curve can be found by simply taking an antiderivative.

To start, let’s first talk about what a definite integral is. A definite integral involves taking an antiderivative and then evaluating the resulting function at certain values. We denote definite integrals in the following notation:

\[\int_a^b f(x)\,dx\]where \(a\) and \(b\) are known as the limits of integration. Suppose the antiderivative of \(f(x)\) is \(F(x)\). Then, that means \(\int f(x)\,dx = F(x)\). A definite integral is the following:

\[\text{if} \int f(x)\,dx = F(x), \text{then}\\ \int_a^b f(x)\,dx = F(b)-F(a)\]This is easiest understood with an example. Let’s try to evaluate the following definite integral:

\[\int_2^5 2x \,dx\]We know from the reverse power rule that the antiderivative of \(2x\) is \(x^2\). So, the definite integral from \(2\) to \(5\) is

\[(5)^2 - (2)^2 = 21\]because we plug in \(5\) and \(2\) into the antiderivative and subtract them.

But what is the significance of a definite integral? Importantly, the definite integral is the area under the curve between the limits of integration. In the last chapter, we found out how to find the area under a curve using the limit definition, but using the definite integral is a lot easier.

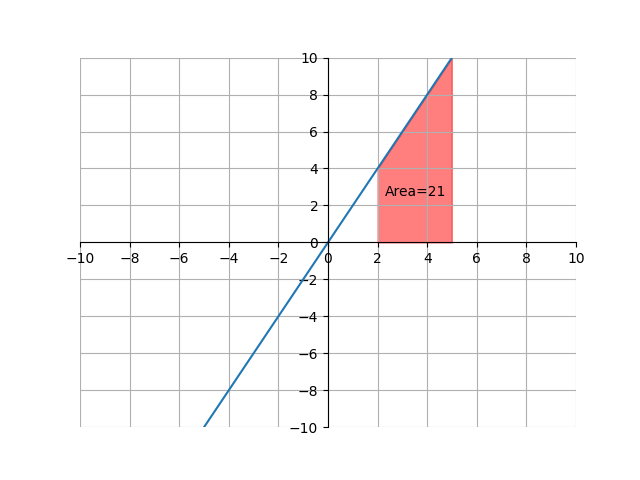

We just saw that \(\int_2^5 2x \,dx = 21\). This means that the area under the graph \(y=2x\) between \(x=2\) and \(x=5\) is \(21\). Shown visually:

Let’s go over one more example of using a definite integral to find the area under a curve. Take the curve \(f(x) = \cos(x)\). What is the area under \(f(x)\) between \(x=0\) and \(x=\pi\)? Turning this into a definite integral, we have

\[\int_0^\pi \cos(x)\,dx = \,\,?\]First, we know that the antiderivative of \(\cos(x)\) is \(\sin(x)\). This is because \(\frac{d}{dx} \sin(x) = \cos(x)\). This means that:

\[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \,dx = \sin(x)\bigg\rvert_0^\pi\]The little bar at the right is known as the evaluation bar. The evaluation bar just means to plug in the top number in for \(x\), and then subtract it by the bottom number. In general,

\[f(x)\bigg\rvert_a^b = f(b)-f(a)\]The evaluation bar is just a way to shorten the expression so there isn’t as much to write. Back to the problem, we have

\[\int_0^\pi \cos(x) \,dx = \sin(x)\bigg\rvert_0^\pi\]which simplifies into

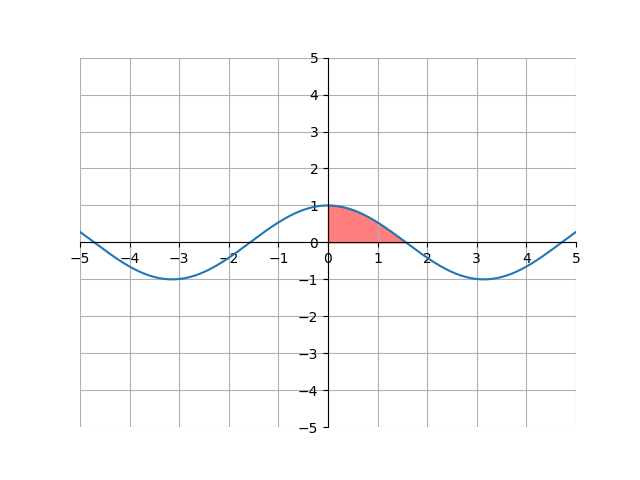

\[\begin{align*} \int_0^{\pi/2}\ \cos(x) \,dx &= \sin(x)\bigg\rvert_0^{\pi/2}\\ &=\sin \left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) - \sin(0)\\ &=1 - 0\\ &=1 \end{align*}\]The corresponding graph for this is:

One final problem: let’s find the area of the same graph, except from \(0\) to \(2\pi\) instead. Setting this problem up, we have

\[\int_0^{2\pi}\ \cos(x) \,dx\]Again, the antiderivative of \(\cos(x)\) is \(\sin(x)\). Now, we can solve this:

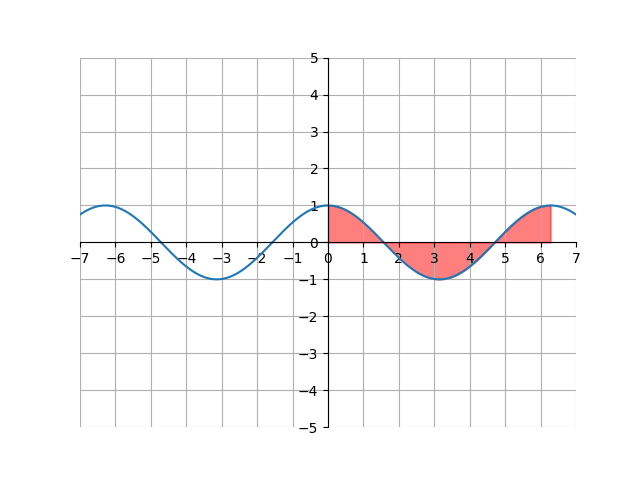

\[\begin{align*} \int_0^{2\pi}\ \cos(x) \,dx &= \sin(x)\bigg\rvert_0^{2\pi}\\ &=\sin(2\pi)-\sin(0)\\ &=0 - 0\\ &=0 \end{align*}\]Why did we get \(0\)? The reason is because the integral returns the signed area, where we subtract any area that lies beneath the x-axis. Looking at the graph, we can see how the answer is \(0\).

Notice how the area above the x-axis and below the x-axis are equal. This leads to the signed area being equal because they cancel each other out.