Calculus I

The Limit Definition of an Integral

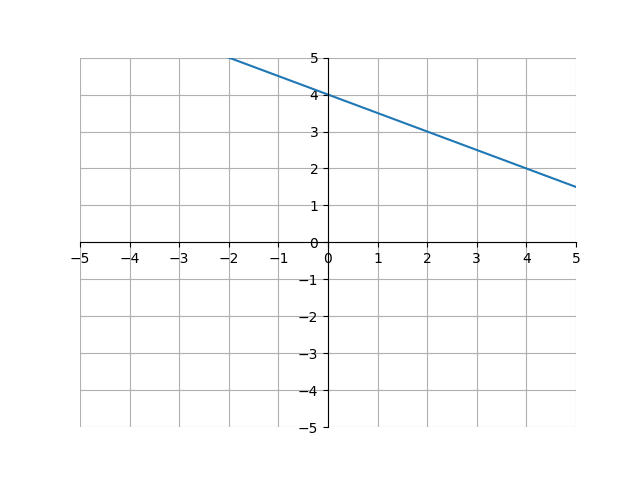

Finding the area under a linear function is fairly easy. For example, take a look at the following graph of \(y=-\frac{1}{2}x+4\):

What is the area underneath the line and between the x-axis, \(x=2\), and \(x=4\)? Here is that region shaded:

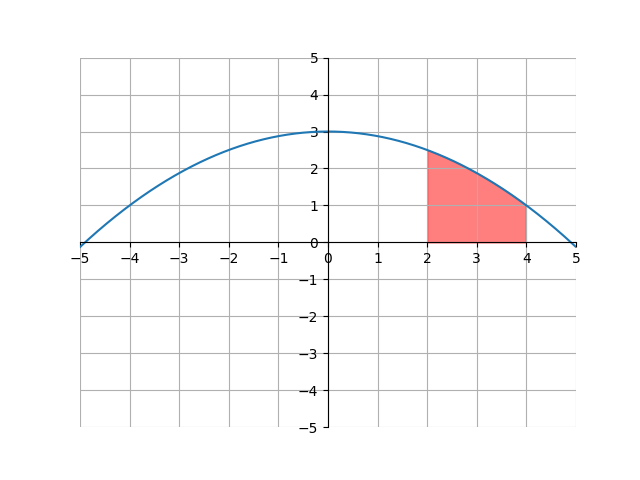

The area of the shaded region is composed solely of a triangle and rectangle, meaning we can just add the areas for those shapes to find the total area. In this case, \((2)(2)+\frac{1}{2}(2)(1)=5\). However, this is not as easy for curves. For example, here is the graph of \(f(x) = -\frac{1}{8}x^{2}+3\) with the same region shaded:

Finding the area of this is considerably harder. Notice that this is similar to the problem we were facing when trying to calculate the slope of a curve - we could find the slope of a linear equation easily, but finding the slope of a curve was considerably harder. Eventually, we were able to formalize that concept to the derivative by using approximations and limits. Here, we will do the same.

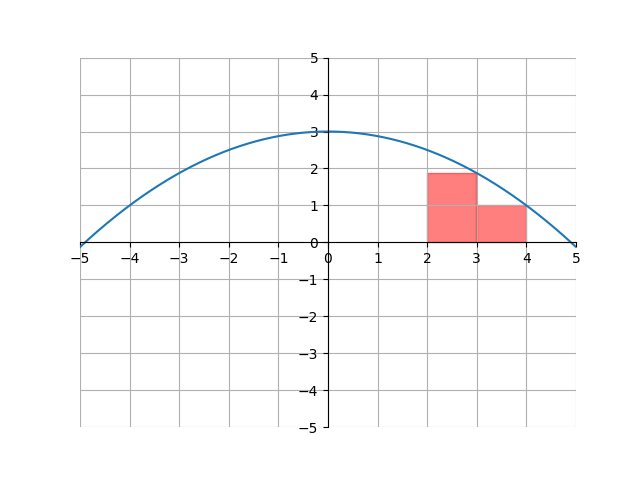

To start approximating this value, let’s start by identifying a shape that we do know how to find the area of. The easiest shape of those is probably the rectangle, because all we have to do is multiply the width times the height. Let’s cover the shaded region with some rectangles:

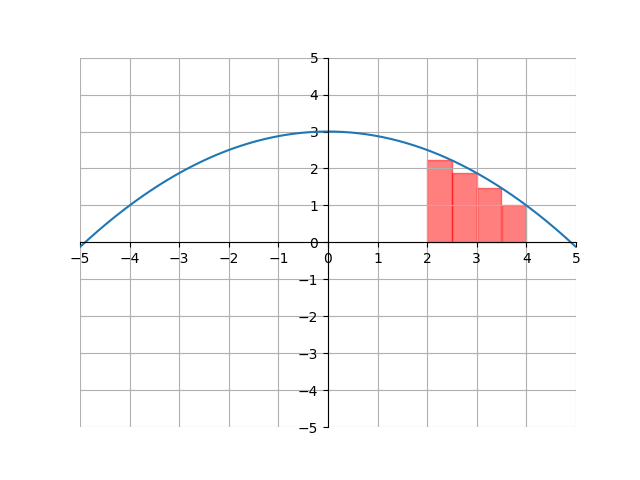

Here, we covered the area with two rectangles, each with width \(1\). This doesn’t solve our problem, because the area covered by the rectangles is a little less than the shaded regions. We can make this approximation slightly better though by increasing the number of rectangles. Here, we have four rectangles, each with width \(0.5\):

The more rectangles we have, the better the approximation will be. This is because the more rectangles we have the total area in the rectangles gets closer and closer to matching the area under the curve.

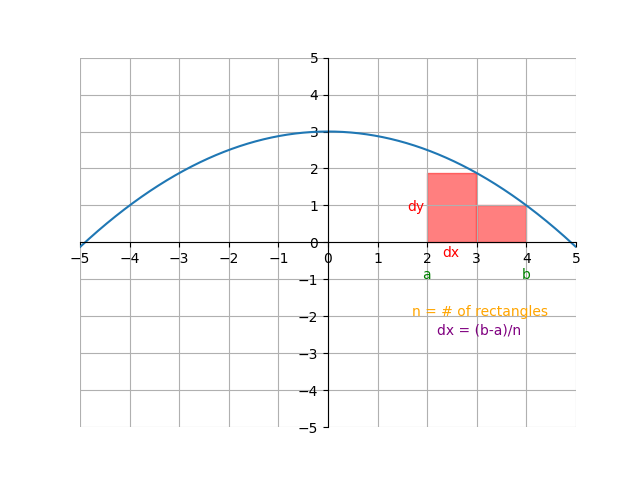

To formalize this problem, let’s add some variables. Let \(A\) be the actual area under the curve, and let \(n\) be the number of rectangles. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be the starting and ending x values of the area we’re trying to find (in this case, \(2\) and \(4\)). Knowing that, we can calculate the width of each rectangle, \(dx\), to be \(\frac{b-a}{n}\).

The reason we call the width of a rectangle \(dx\) is for a similar reason we have \(dx\) in the denominator of the derivative symbol. \(dx\) is supposed to represent a tiny nudge in the x direction, and we want the widths of each rectangle to be as tiny as possible so that the approximation is as accurate as possible.

Now that we have all those variables, we can formalize this by turning it into a formula:

\[\text{Area under curve} \approx (\text{Area of Rectangle 1})+(\text{Area of Rectangle 2})+(\text{Area of Rectangle 3})+\cdots\]We assigned the area under the curve to be \(A\). To find the area of each rectangle, we should multiply each rectangle’s width by each rectangle’s height. The width of every rectangle is \(dx\), but the height varies. More specifically, the height of each rectangle is dependent on the function’s value at the x-value where the rectangle touches the function:

integral.png)

The first rectangle comes into contact with \(f(x)\) at \(x=2.5\), the second rectangle comes into contact with \(f(x)\) at \(x=3\), the third rectangle comes into contact with \(f(x)\) at \(x=3.5\), and so on. This is because the width of each rectangle (or \(dx\)) is \(0.5\). In general, the height for the \(i^{\text{th}}\) rectangle is \(f(a + i\cdot dx)\).

Now that we know that the height of the \(i^{th}\) rectangle is \(f(i\cdot dx)\) and the width of each rectangle is \(dx\), we can finally find the true area underneath the curve. Recalling that \(n\) is the number of rectangles and \(dx\) = \(\frac{b-1}{n}\),

\[\begin{array}{r c c l} \text{Area under curve} &\approx& & (\text{Area of Rectangle 1})\\ & &+& (\text{Area of Rectangle 2})\\ & &+& (\text{Area of Rectangle 3})\\ & &+& (\text{Area of Rectangle 4})\\ & &\vdots& \\ & &+& (\text{Area of Rectangle } n)\\ \end{array}\] \[\begin{array}{r c c l} \text{Area under curve} &\approx& & f(2+1\cdot dx)\cdot dx\\ & &+& f(2+2\cdot dx)\cdot dx\\ & &+& f(2+3\cdot dx)\cdot dx\\ & &+& f(2+4\cdot dx)\cdot dx\\ & &\vdots& \\ & &+& f(2+n\cdot dx)\cdot dx\\ \end{array}\]There’s a clear pattern in the addition here. The only thing that changes from term to term is the number that is being multiplied to \(dx\). We can use summation notation to simplify this formula:

\[A \approx \sum_{i=1}^{n} [f(2+i \cdot dx) \cdot dx]\]Remember earlier that we said that as \(n\) gets bigger, the approximation gets more and more accurate. If we had an infinite number of rectangles, the approximation would be exactly perfect. Thus,

\[A = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} [f(2+i \cdot dx) \cdot dx]\]Remember that \(2\) was just the starting x-coordinate of the area we were trying to find. We assigned the starting x-coordinate to \(a\), so we will use that variable instead. With this, we have found the formula for the area under a curve:

\[A = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(a+i\cdot dx) dx\\\text{where } n \text{ is the number of rectangles}\\a \text{ is the leftmost point for the area}\\b \text{ is the rightmost point for the area}\\\text{and }dx =\frac{b-a}{n}\]The area underneath a curve is known as an integral. This name comes from constructing the area from rectangles and bringing the rectangles closer - or integrating them together - to find the true area. For example, let’s say we wanted to find the integral of \(x^2\) between \(x=1\) and \(x=4\), If we know \(a=1\) and \(b=4\), then \(dx = \frac{4-1}{n} = \frac{3}{n}\)

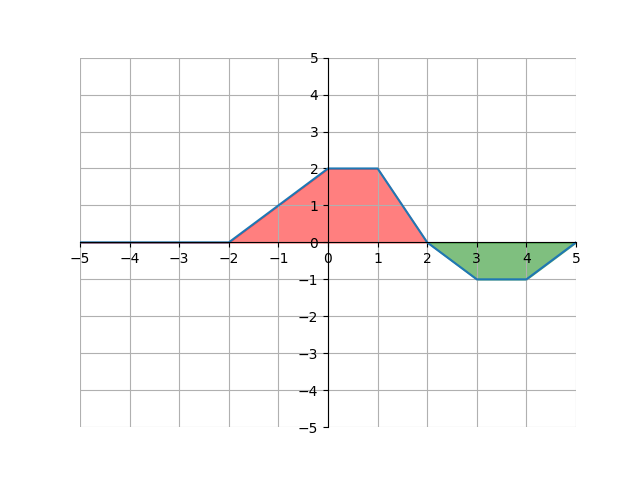

\[A = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(a+i\,dx) dx \\ A = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[\left(1+i\left(\frac{3}{n}\right)\right)^{\displaystyle2} \left(\frac{3}{n}\right)\right]\]One important thing to note is that when we say “the area under a curve”, we subtract any area that is below the x-axis. This is best shown visually:

Here, the total area between the x-axis and the curve between \(x=-2\) and \(x=5\) is \(5+2=7\) but the signed area is only \(5-2=3\). This is because we add the area above the x-axis, and then subtract the area beneath the x-axis. The signed area is the more important one - it’s the value that the above formula returns, and it’s the one that mathematicians use more often.

Actually solving the integral to find the area is very difficult using limits and sums, but in the next chapter, we’ll go over a much easier way.