Calculus I

Limits and Discontinuities

A limit is a fairly simple concept, but is the basis of all of calculus. As the input of a function approaches a certain value, the output of a function will approach some other value - this value is what the limit is.

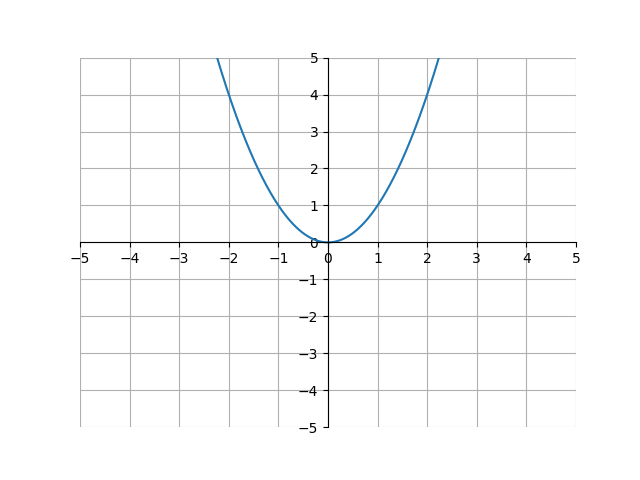

For example, take the following graph of \(x^2\):

As the x-value approaches 2, the y-value of the function approaches 4. This means that the limit of the function as x approaches 2 approaches 4. Or, we can write it with math notation:

\[\lim_{x\to 2} x^2 = 4\]Here, the notation is saying that in the function \(x^2\), as x approaches 2, the function’s value will approach 4. This is an obvious result, because \(2^2 = 4\). However, this is not so obvious for other functions. Take the function \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2}\). What is the limit of this function as \(x\) approaches 0?

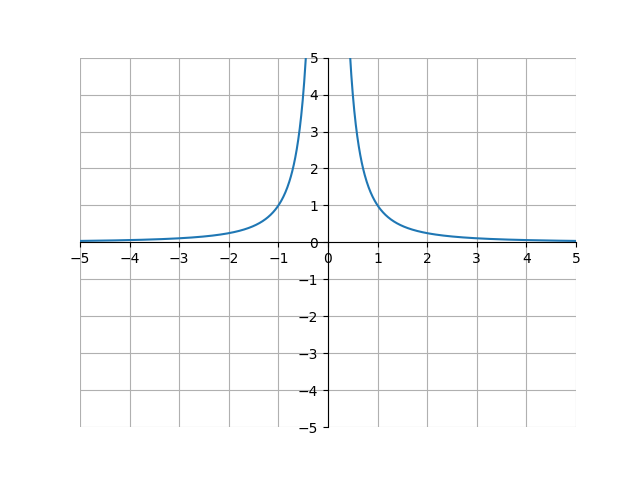

\[\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{x^2} = \,?\]In the earlier problem, we could just plug in 2 to the limit to get our answer. Now, if we plug in 0 this doesn’t work, because \(\frac{1}{0^2}\) is undefined. So, what’s the answer? Well, let’s look at the graph of \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2}\).

Notice how as the x-value approaches 0, \(f(x)\) approaches \(\infty\). Because of this, we can say that

\[\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{1}{x^2} = \infty\]This doesn’t seem right, because we aren’t used to seeing \(\infty\) in equations. However, in the case of limits, it’s fine, because we aren’t saying \(\frac{1}{0^2} = \infty\), we are saying that the limit approaches \(\infty\). Or, in other words, as the x-value get’s closer and closer to 0, \(\frac{1}{x^2}\) gets closer and closer to \(\infty\).

Let’s now look at limits for functions that are discontinuous. There are three types of discontinuities. The first is a removable discontinuity. A removable discontinuity in any function \(f(x)\)is where the limit to a number \(a\) exists, but \(f(a)\) does not.

Let’s see if we can find the following limit:

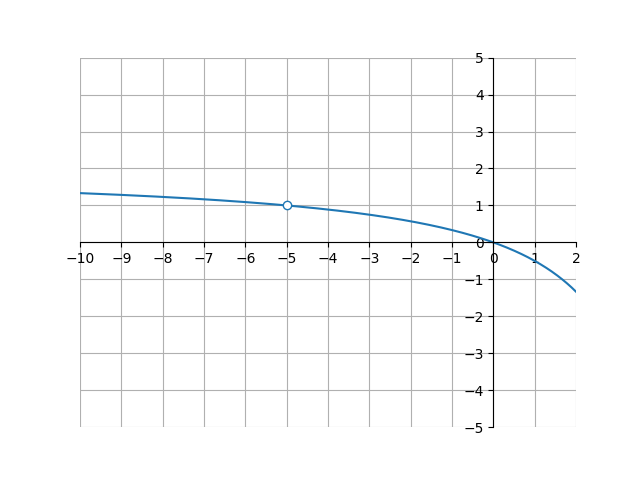

\[\lim_{x \to -5} \frac{2x^{2}+10x}{x^{2}-25}\]Our first step should be to plug in \(-5\). However, after doing that, we get \(\frac{0}{0}\), which does not help us. We can take a look at this graph of \(g(x) = \frac{2x^{2}+10x}{x^{2}-25}\):

The open circle at \(x = -5\) shows that \(g(x)\) does not actually exist at that point (because it is dividing by 0). However, we can see that when \(x = -5\), the y-value approaches \(1\). Thus,

\[\lim_{x \to 5} \frac{2x^{2}+10x}{x^{2}-25} = 1\]That was a removable discontinuity, because despite \(g(-5)\) not existing, \(\lim_{x \to 5} g(x)\) does. If we don’t have a graph for \(g(x)\), we can also use some algebra to get the same answer:

\[\begin{align*} &\phantom{=} \lim_{x \to -5} \frac{2x^{2}+10x}{x^{2}-25} \\ &= \lim_{x \to -5} \frac{2x(x+5)}{(x+5)(x-5)} \\ &= \lim_{x \to -5} \frac{2x\cancel{(x+5)}}{\cancel{(x+5)}(x-5)} \\ &= \lim_{x \to -5} \frac{2x}{x-5} \\ &= \frac{2(-5)}{(-5)-5} \\ &= 1 \end{align*}\]By factoring the numerator and denominator, we can manipulate the expression to get it into a form where we can just plug in the value x approaches without any issue. Manipulation is a rearrangement of certain expressions that does not change the actual value or function, but turns it into a form that is easier to work with. In the above scenario, we manipulated the expression by factoring and then canceling.

Let’s look at another type of discontinuity - a jump discontinuity. A jump discontinuity is where the function seems to “jump” from one point to another. Take the following piecewise function:

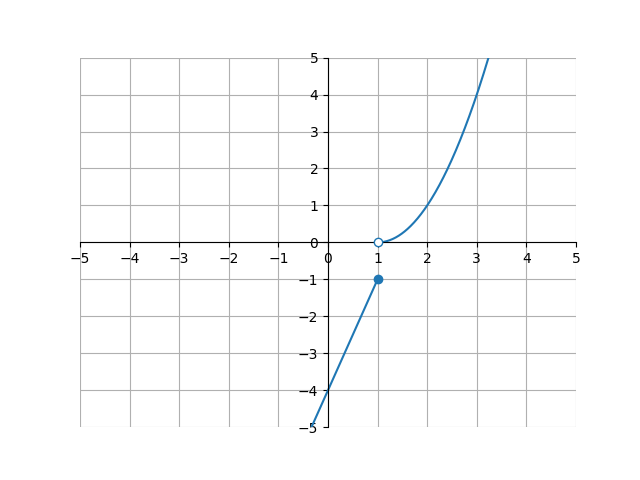

\[h(x) = \begin{cases} (x-1)^2 & \text{if } x > 1\\ 3x - 4 & \text{if } x \le 1 \end{cases}\]On a graph, this looks like

Let’s see if we can find \(\lim_{x \to 1} h(x)\). The issue here is that from the left side of \(x = 1\), y approaches \(-1\). However, on the right side, y approaches \(0\). Because of the discrepancy in the two sides, although \(h(1)\) exists, we say that the limit as \(x\) approaches 1 \(DNE\). \(DNE\) stands for “does not exist”:

\[\lim_{x \to 1} h(x) = \text{DNE}\]We can use some notation to describe the limit approaching from either the left or right side. We said earlier that in the above function \(h(x)\), the left side approached \(-1\) and the right side approached \(0\). We can differentiate these two cases with a small minus or plus sign below the limit:

\[\lim_{x \to 1^-} h(x) = -1 \\ \lim_{x \to 1^+} h(x) = 0\]The minus sign means the limit as \(x\) approaches 1 from the negative (or left) side. The plus sign means the limit as \(x\) approaches 1 from the positive (or right) side. We can also use this notation to say

\[\text{If } \lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) \ne \lim_{x \to a^-} f(x) \text{, then } \lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \text{DNE}\]where \(a\) is any number and \(f\) is any function.

Take a look at the following function:

\[i(x) = \begin{cases} 2 & \text{if } x \ne 3\\ 4 & \text{if } x = 3 \end{cases}\]The graph of \(i(x)\) is

What’s the limit as x approaches 3? Despite \(i(3)\) equalling 4, the correct answer is \(2\). This is because we aren’t looking for \(i(3)\), we are looking for the value of \(i(x)\) as \(x\) gets closer and closer to \(3\). And as \(x\) gets closer to \(3\), \(i(x)\) gets closer and closer to \(2\).

Here’s another example of a discontinuity:

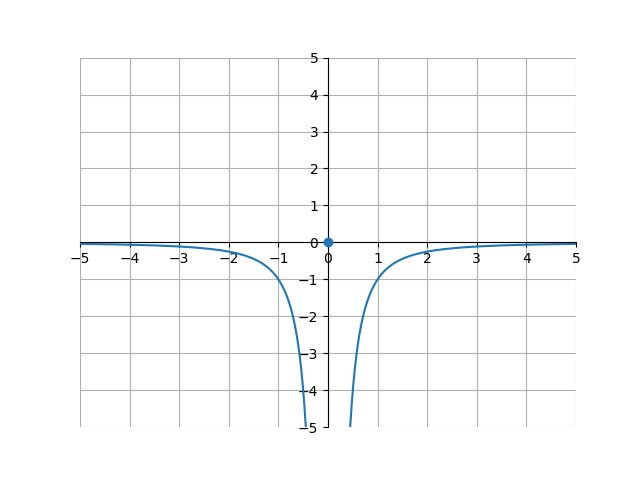

\[k(x) = \begin{cases} -\frac{1}{x^2} & \text{if } x \ne 0\\ 0 & \text{if } x = 0 \end{cases}\]

Both \(\lim_{x \to 0^-}\) and \(\lim_{x \to 0^+}\) equal \(-\infty\). Because of this, we can say that \(\lim_{x \to 0} = -\infty\). The fact that the \(k(0) = 0\) does not matter, because we are simply looking for the function value as \(x\) approaches 0, not when \(x\) equals 0.